Lester Butler died 25 years ago, on May 9, 1998. In the years since, blues fans have wondered what happened the weekend that he was killed.

Now, for the first time, No Fightin’ ties together all of the stories, all of the details of that fateful week in May of ’98. Using archival interviews, court documents and new sourcing never before published, No Fightin’ is able to present the most thorough and complete accounting of the final days of Lester Butler.

$5,000 to burn

It wasn’t a perfect gig, with some technical glitches — a damaged snare drum, a broken bass string — but the crowd assembled didn’t care. Lester Butler and 13 tore the house down, and everyone in the building knew it.

Onstage was a cavalcade of guests, representing Butler’s past and present. But make no mistake, Butler was the star.

It was a special night in Ospel, and would take on near-mythical status because of what would transpire over the next eight days, a macabre and bizarre crime that would be the death of Lester Butler.

Trouble began almost as soon as 13 and friends came off the Moulin Blues Festival stage on May 2, 1998. The band’s van was parked behind the stage and, rather than making for a quick getaway, the festival-closing 13 got blocked in by crew trucks there to tear down the show. With nowhere to go until the trucks were packed, the band went stir crazy. 13 wouldn’t leave the venue until hours later.1

The musicians finally reached their rooms about an hour-and-a-half before shuttles were scheduled to pick them up at 6 a.m. for an 8 a.m. Sunday flight.1

On the flight home, Butler told guitarist Alex Schultz that he intended to get an eight-ball of cocaine when he got back to California. “He had five thousand dollars burning a hole in his pocket, and what he did was stay up for five days straight,” Schultz told Classic Rock magazine in 2014.2

This fit a pattern, Butler’s sister Ginny Tura said.

“He would have a binge, I would say, about once a year when he would drink and do drugs,” Tura said of her brother. “Usually after he came into big money for his music.”3

A headlining gig at a European festival would fit that description.

Butler had fits and starts with sobriety, and he seemed to understand the effect of a drug binge on someone who had been sober.

“I love my brothers in NA, but I’ve lost more friends coming out of rehab because of its spring effect,” Butler told New Zealand’s The Real Groove in a 1997 interview. “Rehab crushes that spring down, and then they get out, and booiinngg! It’s really sad.”

After a long layover in Chicago, Lester Butler finally arrived at LAX, back on his home turf.1

A bad fix

A couple of days later, on Tuesday, May 5, 1998, Eddie Clark got a call.

“About Tuesday he called me about 2 a.m.,” Clark recalled in an email to NoFightin.com. “… He asked me if I was going to be OK if anything ever happened to him. Yes, Lester. I had just gotten married [on] April 2, 1998, so I said yes things will be fine, see you on Friday.”

It would be the last time Clark spoke to Butler.

13 had its first post-tour gig booked for Friday, May 8, at Jack’s Sugar Shack in Hollywood, on a triple-bill with Groovy Rednecks and Spaghetti Western.

As his band — on this night, guitarist Chris Masterson, bassist Mike Hightower and drummer Clark — set up to play, Butler was missing.1

Lester would never make it to the stage, with the events leading to his death already in motion. Though accounts vary, there are a few key pieces that create a picture of that tragic weekend.

On the evening of May 8, rather than go to his own gig, Butler instead went to the Hollywood home of his former Red Devils bandmate, Bill Bateman. There was another person there: April Ortega.3

“He’d been smoking rock, snorting coke, taking downers and drinking rum, so he was high,” Bateman told Classic Rock. “The two of them were sat in my living room and Lester was begging her for an injection of heroin, rather than snorting it like he had been.

“Eventually she did and he OD’d,” Bateman said. “I was high myself by then and wasn’t paying them much mind.”

“He would have a binge, I would say, about once a year when he would drink and do drugs. Usually after he came into big money for his music.”

Ginny Tura

It is unclear why Butler needed Ortega to shoot him up, rather than fix himself.

It has been speculated that Butler’s tolerance for the drug was low because he had been clean for awhile.4 Or maybe mainlining the dope was too much all at once; maybe it was too strong for anyone.

Butler passed out.3

At this point, Ortega’s boyfriend, Glenn Demidow — who either arrived at Bateman’s or was there the whole time, depending on the source — tried to revive Butler by injecting him with cocaine.

Bateman said the pair shot Butler’s cocaine through the veins in his hand.

“They had the idea that this would bring him back, and it killed him,” Bateman said.2 Butler may have been injected with coke three times in a futile attempt to revive him, according to one account.5

Unsurprisingly, he did not regain consciousness.

Ortega and Demidow then carried Butler’s lifeless body and placed it into his own van. They got in and drove off.3

The weekend was just getting started.

Charmed life

The legend of Lester Butler — to his fans, and maybe to his friends — was built partially on a myth of his excesses and close calls. To find him passed out, or in need of medical care, did not seem to be an unusual occurrence.

In a 1997 interview with The Real Groove, Butler described it in his own words.

“You wanna know the truth? I died legally,” Butler said. “I was lying on the table, cold blue, out — ‘Oh, he’s gone, we electroshocked him, we have adrenaline, he’s gone, he’s dead’.”

Butler had so many near-death experiences that Bateman apparently started keeping count.

“We were rowdy guys,” Bill Bateman told Classic Rock about The Red Devils. “… One of us was bound to end up dead. Lester had actually clinically died four times in previous years. On one occasion he woke up in the morgue with a sheet over his head. It was his opinion that he led a charmed life.”

Between late that Friday night, May 8, and Saturday night, May 9, Butler’s body was on the move, taken from location to location by Ortega and Demidow.

There was no charm to what was happening.

This was no romantic Gram Parsons story, whose hijacked corpse was cremated in a funeral pyre in Joshua Tree by Parsons’ faithful — if criminally misguided — friends.

What happened to Lester was brutal, abusive and miserable.

‘God bless you’

While Ortega and Demidow roamed the streets — with Butler an unwilling passenger — 13 were working at Jack’s Sugar Shack as a trio. They were probably wondering where their frontman was, and probably not shocked that he wasn’t there.

But what happened next is hard to fathom.

“Well, it was tense on Friday, Lester was not showing up, but finally here comes that funky blue Dodge van we used, but Lester was not driving,” Clark wrote.1

While a comatose Butler lay in the van, Ortega and Demidow went into the bar to watch 13 play. They told people at the club that Butler passed out and was sleeping it off.6

“So, the van and strange people driving and passenger, Lester was in the back passed out. I’ve seen it before, let him sleep it off … or better yet, take him to the ER,” Clark wrote.1

Yeah, they weren’t going to the ER.

On message boards and email lists, an anonymous account was posted and widely circulated in late 1998. This message, blunt and violent, became the “facts” of the case, as most know it:

“Lester still hours later wasn’t able to wake himself (would you with 5 doses of deadly drugs in your system?). They still didn’t get him medical help but instead took him to their apartment at 2am, they went to sleep, then the next night after he had died in their care dropped his dead body back at Bill B.s house. They were literally at the house 2 minutes just to dump the body and then drive away in Lester’s van. Lester’s body was put in a guest bed to look as if he had died in his sleep.”

Meanwhile, on May 9, 13 prepared for its gig that night at Killian’s in Torrance, California, assuming that Butler had come around from being “passed out” the night before.

“Well, at that time, it was thought Lester was taken to the ER, so Killian’s maybe was on, I showed and Mike showed, Chris didn’t, so I left to go back to Santa Barbara and left Lester’s stuff there,” Clark wrote.1

Lester Butler’s body was discovered — apparently by another, unnamed friend, apparently at Bateman’s — early on Sunday, May 10 … Mother’s Day.5

Bateman picks up the story.

“(Ortega and Demidow) took him in his van to their house and he died there,” the drummer recalled. “After he’d been dead for eight hours they dropped him off at my place again, and I took him to the hospital. Then the cops turned up.”

Lester Butler was pronounced dead at Los Angeles County Hospital. He was only 38 years old.3

Police told Ginny Tura that someone had written a message on her brother’s body: “I am fucking stupid.”3

In his datebook, where he kept detailed notes on all of his gigs, Clark wrote under May 9, 1998: “Killian’s. So long Lester God Bless You.”7

Unorthodox death

That weekend, word spread through the blues grapevine. For much of the world, news of Butler’s death came via email newsgroups, primarily the “Blues List” and the “Harp List” — Blues-L and Harp-L.

Many who were around in that era will remember an email from Sunday, May 10, 1998, from Dave Melton, with the subject “Lester Butler Has Passed.” It hints at the seedy, “unorthodox” nature of his death:

I have spoken in some length with Eddie Clark, drummer for Lester’s Band and a long time friend of mine. Details are still sketchy as to exactly what happened, except unfortunately I can confirm that Lester passed away apparently from an overdose of heroin. There is a criminal investigation in progress, due to the unorthodox circumstances concerning his death.

Melton said that musicians were gathering at an Alex Schultz gig that night in West Los Angeles.

Years later, Schultz thought back on his friend.

“I didn’t have the sense that (Butler) meant for it to end the way it did, but at other times he was pretty fatalistic,” Alex Schultz recalled to Classic Rock. “I think he felt there was a destiny he was living out — that he was going to go out that way.”

Guitarist Greg “Smokey” Hormel traces Butler’s bleak prognostication back to the harp player’s earliest days in blues. A month after Butler’s death, in a June 8, 1998, interview with American Music, Hormel made the connection to Butler’s mentor, Michael “Hollywood Fats” Mann, the legendary guitarist who died in 1986 at age 32.

“In the last six months (Butler) was sober and he was a great guy. I was hopeful for him and thought his career was going to have a second renaissance. But when I heard he OD’d, I wasn’t surprised,” Hormel said.

“He had this weird idolization of Hollywood Fats and that’s where he developed his drug habit. They always hung out together and he said he was going to go like Hollywood Fats, and he did. I do remember him fondly.”

Aftermath

Confusion, devastation and disbelief, in equal measures, colored the days and weeks after Butler’s death. The primitive World Wide Web of 1998 allowed enough connection for Butler fans to find each other, but not enough reliable accounts to be able to make sense of the incident.

Each scrap of new information was another painful cut.

The May 12, 1998, Long Beach Press-Telegram blared the headline, “Blues artist Lester Butler dies of drug overdose”:

“Lester Butler, the extraordinary blues artist who’s sung and played harmonica with such major stars as Mick Jagger, Bruce Willis and Stevie Wonder while fronting his own groups, including the Red Devils, the Accelerators and, most recently, 13, died Saturday night in Los Angeles of a heroin overdose.”

The Los Angeles Times on May 15, 1998, was more measured in its verdict: “causes to be determined after an autopsy.”

Billboard magazine gave Butler’s death a paragraph’s mention, but got his age wrong.

The observations and updates of Dave Melton, a California guitarist who played with Butler, were crucial in these early days.

“Lester’s death is now classified as a homicide, and several people have been arrested and are being questioned by the police,” Melton wrote to the Blues-L on May 13, 1998.

Family, friends, fans and fellow musicians gathered Thursday, May 14, for a public viewing at Gates & Kingsley mortuary in Santa Monica.

“The funeral itself is private as far as I know, and his body will be cremated and ashes spread out in the ocean,” Melton wrote.

“(I)t was strange to see him like that, but I had to go and do it. Seems like we just went through this with William Clarke. I briefly spoke to Larry Taylor, Lynwood Slim, Alex Schultz and a few others that were arriving and leaving. (it was merely a viewing and not an actual funeral, that will be private).”

The anonymous online postings continued to offer a hazy chronology of events, almost as they happened in 1998. These posts took up the spaces where factual reporting was missing, becoming the de facto narrative in the case of Lester Butler, repeated and repeated.

“After receiving toxicology reports from the Coroner, the detectives picked April up as she walked out of a drug center w/Bill B. weeks after Lester’s murder,” one unsigned post read. “Glenn fled but finally turned himself in to his lawyer weeks after April’s arrest (nice boyfriend, huh?)”

With Ortega and Demidow in custody, the story turns from mourning Lester Butler to a search for justice.

Like so much of this story, things don’t always turn out as expected.

Defendant 1 and 2

Not much is publicly known about two of the central figures in this story, Glenn Demidow and April Ortega.

Their story has been told in second- and third-hand accounts, with only speculation or guesses to their motivations and actions on that May weekend in 1998.

Court records from the Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles, provide more details into the case and its aftermath, 25 years later. The court proceedings reveal only the barest evidence of Demidow and Ortega telling their own stories.

Both April May Ortega (Defendant No. 1) and Glenn Demidow (Defendant No. 2, alias “Glenn Michael Palmer”) were charged in Butler’s death. The violation date is given as May 8, 1998, in court documents — the Friday that the whole mess started.

Charges were filed on June 17, 1998.

Ortega was preliminarily charged with three felonies related to Butler’s death: Murder in the first degree, in violation of Penal Code section 187(A), and two counts in violation of the Health and Safety Code section 11352, which makes it a crime to sell, give away or transport a controlled substance. She pleaded not guilty to the murder charge, and did not enter pleas for the drug charges, according to court records.8

Demidow was also charged with first-degree murder, along with one count in violation of California’s Health and Safety Code section 11352. He did not enter pleas, according to court records.

“The two of them were sat in my living room and Lester was begging her for an injection of heroin, rather than snorting it like he had been. Eventually she did and he OD’d.”

Bill Bateman

Neither faced charges related to taking the van or moving Butler on May 8 and 9. No one else was charged; the focus was on the two people who administered the lethal combination of heroin and cocaine by injection.

The murder charges carried a term of 25 years to life in state prison, and a fine of up to $10,000.

According to reporting in “The Greatest Music Never Sold,” Ortega and Demidow in court claimed they had not taken Butler for help because they were afraid he would get in trouble.

With jury trials set, on Nov. 17, 1998, Demidow and Ortega instead both took deals, and pleaded guilty to lesser charges of involuntary manslaughter. The other, more serious charges, were dropped by prosecutors.

The next day, Nov. 18, Ortega was sentenced to two years in state prison; Demidow got three.

Five years … seemingly one year for each injection of heroin or cocaine.

Only Butler got the life sentence.

Legacy

Though the combined five years in prison wasn’t what family and friends hoped for, the verdict did offer some bit of closure. With the guilty pleas, Lester Butler, legally, did not die by an overdose — he was killed by an overdose. He was the victim of a crime.

The truth offered cold comfort.

Some fans were drawn by what they saw was the drama and the folklore of the doomed bluesman, the devil come to collect on Butler’s contract to play the harmonica with fire and passion. Shrouded in black, with satanic and drug imagery all around him, Butler attracted and appeared to revel in that mystique. Fans looked at songs such as “Devil Woman,” “Pray For Me” and “Plague of Madness” (“I’m into homicide … you better watch your back!”) as beyond autobiographical — they were nearly prophetic.

But the real Les was no shaman, and his legacy goes beyond his image and even his music.

In their memorial card, his family wrote, “He leaves his mother Patricia Butler, sisters Ginny Tura and Cathy Buinauskas, nieces April and Malone and nephew Drew, long-time companion Lori Peralta and many friends and fans. …

“Lester, who grew up in Santa Monica, began playing harmonica at the age of six and has loved it ever since. He said, ‘It’s a hard life playing music for a living but on the other hand, I’d rather be happy being poor and playing music for the rest of my life’ and credits ‘the healing force of the Blue.’

“He will be missed but never forgotten. We love you Lester!”

Lester Butler: The unplayed gigs

After 13’s triumph at the Moulin Blues Festival, it was back to the U.S., and back to hustling on the local circuit for a while.

The band had two weekend gigs lined up for their return:

- Friday, May 8, at Jack’s Sugar Shack in Hollywood, on a triple-bill with Groovy Rednecks and Spaghetti Western.

- Saturday, May 9, at Killian’s in Torrance, California.

Butler was a no-show. The remaining 13 members — guitarist Chris Masterson, bassist Mike Hightower and drummer Eddie Clark — played on Friday night, but canceled the Saturday gig.

After his death, gigs that Butler had on the books turned into hastily arranged memorial jam sessions. 13’s Friday, May 15, slot at Cafe Boogaloo in Hermosa Beach turned into the first of those special get-togethers.

“The band consisted of Chris Masterson on guitar and vocals, Alex Schultz was also on guitar, Eddie Clark was on drums and Mike Hightower on bass,” Melton wrote on May 16. “Enrico Crivellaro also sat in, as well as former Canned Heat bassist Mark Goldberg. Randy Chortkoff and Jimmy Z sat in and played some harmonica.”

A similar event was planned for Wednesday, May 20, at the Blue Cafe in Long Beach. Clark noted a “farewell to Lester” gig at Killian’s on May 23.7

The Paradiso in Amsterdam, the site of several Red Devils and 13 gigs, arranged a Lester Butler memorial on June 9, “featuring Butler songs played by Paladins and others,” according to a mention in the June 4, 1998, de Volkskrant.9

Meanwhile, Lester Butler’s longtime friend, Hook Herrera, played two tribute shows in honor of Butler: June 19 at Cafe Boogaloo, and June 20 at the Blue Cafe.

Perhaps more upsetting: Not all local newspapers changed their calendar mentions, and touted Butler gigs upcoming, even after he had died:

- The May 28 Los Angeles Times listed Lester Butler as playing a Saturday, May 30, gig at Hop City Blues and Brew in Anaheim.

- On June 25, the Times calendar alerted fans to a Lester Butler & 13 gig at Dixie Belle in Downey, California, on Saturday, June 27.

“Some of the musical friends of the late Lester Butler are getting together to jam in his memory; the show will feature Smokey Hormel and Steven Hodges, as well as former members of Lester Butler’s band,” Mary Katherine Aldin wrote in the June 26 issue of LA WEEKLY about that Dixie Belle gig.

Ed Boswell was the promoter at Dixie Belle, and booked the June 27 show months in advance.

“I felt there was some kind of irony that he didn’t play there. He didn’t make it, but his friends can make it for him,” Boswell said in a June 26, 1998, interview with the Long Beach Press-Telegram. “Maybe he could be there in spirit.”

To mark what would have been Lester Butler’s 40th birthday, his friends and family organized the “Badass Birthday Blues Bash, Tribute to Lester Butler” in 1999. On Nov. 12, Butler’s birthday, it was featured artist Finis Tasby leading the charge at Cafe Boogaloo. Top Jimmy was the featured artist at the Nov. 13 (Lester’s “favorite number”) tribute to Butler the next night at Blue Cafe.

A flier for the weekend lists a who’s who of blues artists who were invited to perform and reminisce: Smokey Hormel, James Intveld, Randy Chortkoff, Alex Schultz, Larry Taylor, Steven Hodges, Mark Goldberg, Andy Kaulkin, Johnny Bazz, Jerry Angel, Eddie Clark, Darren Simonian, Mitch Kashmar and others.

These would be the last tribute shows to Butler until the early 2000s, when the Lester Butler Tribute Band assembled in Europe for a series of performances. Since then, memorial shows and tribute bands have sprung up around Butler. Even as recently as February 2023, Lester Butler tribute events were being organized in the Netherlands.

The Lester Butler story is full of missed — or squandered — opportunities. In a May 1998 obituary in her Delta Snake Daily Blues News column, writer Char Ham mentions a what-could-have-been opportunity for Butler and 13:

“The 13 Band had just returned from Europe, where they tore up the festival scene, supporting Jimmy Vaughan and B.B. King,” Ham wrote in the obit, which was cross-posted on a blues email list. “Sadly, Butler never found out that upon the band’s return, they received an offer to open for Van Halen at a festival in Holland in June.”10

Footnotes

(1) Eddie Clark email to NoFightin.com, Jan. 22, 2023.

(2) “Fear and loathing in Hollywood,” by Paul Rees, Classic Rock magazine No. 195 (2014). A version of this story, “Blues, drugs, fights, cops, jail, death: the incredible story of The Red Devils,” was republished on loudersound.com on Nov. 5, 2019.

(3) “The Greatest Music Never Sold” by Dan Leroy, 2007.

(4) From loudersound.com, Nov. 5, 2019: “Ginny Tura challenges Bateman’s account of her brother’s last hours and also the notion that he’d careened out of control. ‘Lester was sober for many years, and this relapse was fatal because his tolerance was low,’ she maintains.”

(5) “Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars,” by Jeremy Simmonds, 2008.

(6) A widely circulated, anonymous posting online in late 1998 said that, after Lester Butler was dosed, “April and Glenn then drove him to his gig and left him in his van (unconscious) while they went in and listened to Lester’s band (without Lester) telling people that HE had passed out and was sleeping it off.”

(7) From Eddie Clark’s 1998 “pocket pal” datebook, provided by Clark to NoFightin.com.

(8) From the state of California penal code, Chapter 1 — Homicide: 192: Manslaughter is the unlawful killing of a human being without malice. It is of three kinds: (a) Voluntary — upon a sudden quarrel or heat of passion. (b) Involuntary — in the commission of an unlawful act, not amounting to a felony; or in the commission of a lawful act which might produce death, in an unlawful manner, or without due caution and circumspection. This subdivision shall not apply to acts committed in the driving of a vehicle. (c ) Vehicular.

(9) “Lester’s Legendary Last Gig” might not have been his final appearance onstage. NoFightin.com reader Jeroen said that Butler sat in with the Paladins at a concert in de Effenaar in Eindhoven, NL, on May 3, 1998, the day after the Moulin Blues Festival. This gig has not been confirmed by NoFightin.com.

(10) It is unclear what Van Halen gig this could have been. There was a June 7, 1998, bill in Denmark featuring Van Halen, Joe Cocker, Alice Cooper and a Danish band called Big Fat Snake – maybe the slot that was earmarked for 13? Ironically, but maybe appropriately for Butler’s luck, Van Halen had to cancel its June Europe tour that year due to an injury to Alex Van Halen.

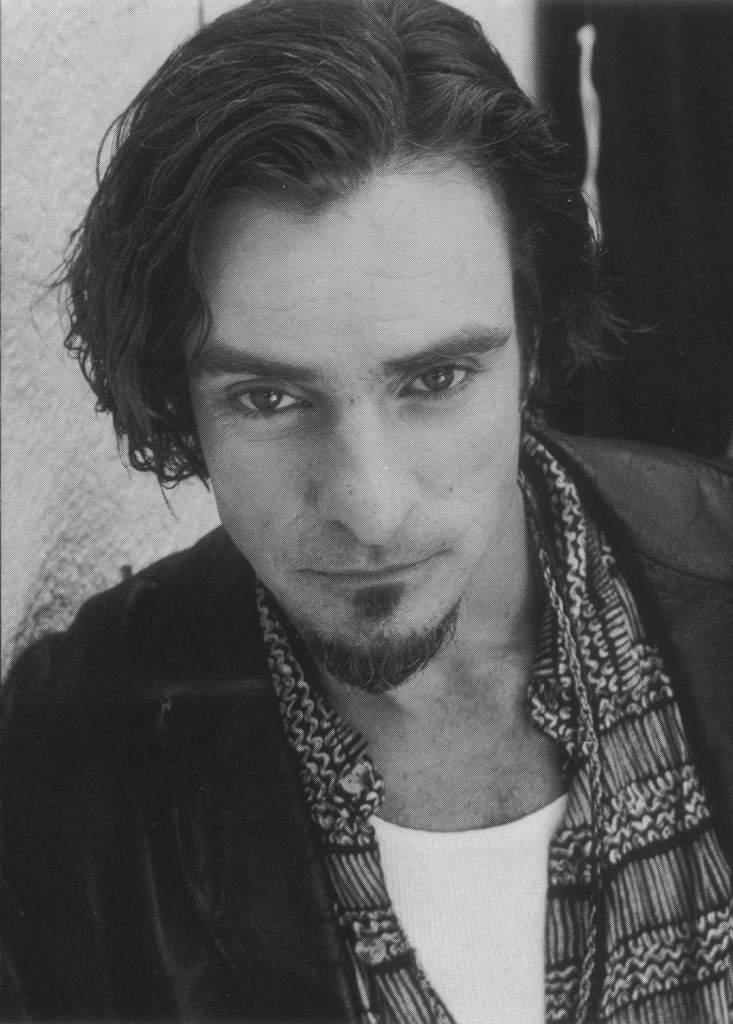

Top image: Photo by Rens Horn; photo illustration by NoFightin.com.

Make a one-time donation to NoFightin.com

Make a monthly donation to NoFightin.com

Make a yearly donation to NoFightin.com

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated. All proceeds go to the maintenance and upkeep of NoFightin.com

Your contribution is appreciated. All proceeds go to the maintenance and upkeep of NoFightin.com

Your contribution is appreciated. All proceeds go to the maintenance and upkeep of NoFightin.com

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly